The COVID-19 lockdown rendered UK celebrations of the 75th anniversary of VE Day this month low key, if not non-existent, prompting many Britons to compare England Then with England Now.

A Guardian writer complained that, "Britain was led by Churchill then – it's led by a Churchill tribute act now." At the increasingly essential upstart UnHerd.com, Gavin Haynes observed:

"Many seem to have been waiting their whole lives to know what they would have done during the Blitz. Now we have our answer: 750,000 NHS volunteers inside a week, ungrumbling financial hara-kiri by small businesses, and fistfuls of notes shoved down the negligée of Captain Tom. We're amazing. But in our heightened state, we're also at the whim of various madnesses of any number of crowds."

A very British sort of "madness," though. In a recent poll, over 80 per cent of Brits were in no hurry to lift the lockdown. "Whatever happened to dissent?" wondered Lionel Shriver as she surveyed this unedifying spectacle of paralysis. To which I'd reply, "What dissent?"

In the roughly 20 years that I've been reading the English press online, the two most frequent comments below the "latest outrage" articles have been, "This political correctness business is getting out of hand!" and "Someone should do something about this!"

First off: Getting out of hand?

Worse, appending exclamation marks to one's own admissions of blindness and lack of agency inadvertently makes such statements seem all the more pathetic.

Surely this wasn't the same race that stoically survived Hitler's relentless bombing campaign?

Well, here's my blasphemous theory:

That the British "default setting" is resigned inertia and conformity, their widely-reported tolerance for eccentrics being merely the exception that proves the rule; "tall poppy syndrome" is their more typical impulse.

(And yes, I know where the tradition comes from, but have always smiled ruefully inside about the fact that snipped off poppies became the semi-sacred symbol of Remembrance Day....)

The English's vaunted bravery during the Blitz was simply an in extremis extension of their normal "mustn't grumble" and "know one's place" temperament, punctuated by the occasional inane, forced-march "cheerful" tune, depicted here in a more recent iteration.

But during the war, the world got to watch this national temperament in "action," and quite naturally misinterpreted it as stoic courage, what with all that rubble laying around.

Speaking of which: That famous photo of a milkman matter-of-factly going about his daily rounds amidst crumbled London buildings was staged.

Why be surprised? These were the same people, after all, who'd ingeniously mythologized what by any historical standard was an abject defeat — the Dunkirk retreat — into an admittedly thrilling tale of victory.

And so it continues:

"'Stay alert!'" writes Peter Franklin this week, pondering at the latest English lockdown slogan. "Sounds exciting, doesn't it? A definite hint of derring-do.

"Real life, though, is far from adventurous. Forget 'stay alert' – for most of us it's still 'stay at home.'"

And again: four out of five Britons say they are perfectly happy to do so.

But what about those "Keep Calm and Carry On" posters? some of you are asking. These nostalgic relics, we're told, perfectly embody the English home-front spirit throughout WWII.

Yeah, no.

Churchill's Ministry of Information printed those posters, but they were never plastered up. We only know about them because one copy was discovered in 2000 in a used bookstore, then put on display behind the cash register. The rest is pop culture history.

The remaining "Keep Calm and Carry On" posters were pulped, having been judged inappropriate, while the Ministry tried out other propaganda slogans, with varying degrees of success:

"Freedom Is In Peril" was also deemed ineffective, blamed on "the abstractness of the words, not one of which had any popular appeal."

"Even during the planning stages the criticism had been raised that "Freedom" was rather an abstract concept and was "likely to be too academic and too alien to the British habit of thought."

See what I'm getting at?

In the 1960, the Beyond the Fringe comedy troupe dared to poke fun at their countrymen's self-mythologizing, in a highly contentious long-form sketch called "The Aftermyth of War." All four members were born in England during the conflict, and the sketch gives the impression that one has peeked into a nursery where children are play-acting overheard (but not quite understood) radio bulletins, newsreel clichés and the worried whispers of grown-ups.

And the skit's running punch line, uttered in response to serial atrocities?

"You put on the kettle, and we'll have a nice cup of tea."

At the very same time, a couple of British kids were going even further than the Fringe.

Kevin Brownlow, who'd conceived an idea for a film when he was only 18, teamed up with 16-year-old Andrew Mollo to write and direct a daring alternative history of the war.

It wouldn't be the first one ever made. One of Ealing Studio's contributions to the war effort, the highly regarded Went the Day Well?, depicted a pastoral English village invaded by Germans who were fought off by plucky townsfolk.

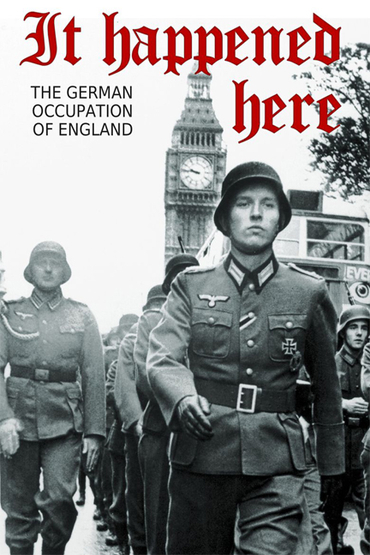

With the war over but still in the rear-view mirror, young Brownlow and Mollo veered in the opposite direction. Released in 1965, their movie It Happened Here was the fruit of eight years of amateur labour (albeit with assists from established directors Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson and especially Stanley Kubrick, who donated the short ends of film stock left over from Dr. Stangelove.)

In this 1945 England, VE Day never came. The Nazis took advantage of Dunkirk to invade. Great Britain is occupied, "governed" by the British Union of Fascists. Partisan resistance is relatively miniscule. Indoctrination is widespread, as is collaboration. The citizenry are pretty much content to enjoy a "quiet life" again, whoever happens to be in charge.

After witnessing the death of friends at the hands of the resistance, an Irish nurse is evacuated to London. At first she tries to remain apolitical, but the more she experiences life under occupation, the less she likes it.

Note how frequently this trailer asks, "Would YOU collaborate?" The same question would be unthinkable in a similar American film, presuming one would or could even be made.

Note too that Brownlow and Mollo called their film It Happened Here; even raving leftist Sinclair Lewis was still American enough to stick an admittedly sarcastic "Can't" in the title of his fictional anti-fascist fantasia.

(As Tom Wolfe quipped, "The dark night of fascism is always descending in the United States — and yet lands only in Europe.")

I also wonder if you could get almost 1,000 unpaid actors and extras in the United States circa 1945 to enthusiastically either put on Nazi uniforms and parade down a New York City street — one thinks of Rick's retort to Major Strasser's pointed question about his hometown in Casablanca — or remain in civilian clothes and cheer them on, as seen throughout It Happened Here.

(Amusingly, a bunch of Italians mistook that fake newsreel for a genuine, previously unknown Nazi propaganda film, and aired a "documentary" about their "discovery" on national television.)

I wish I could tell you that It Happened Here is a masterpiece. In so many ways, the story of the making of the film is much more compelling than the movie itself.

Lest you think cosplay is a 21st century fad, for example, many of those extras were British science fiction fans, who were thrilled to get to wear Mollo's accurate and believable uniforms.

Then there's this:

"[Brownlow] claims that one of the extras on the film asked to borrow a swastika flag from the props department to take to a party to which Brownlow and Mollo were then invited. They arrive intrigued, a little dubious, and are shocked to find they're at a gathering of British fascists celebrating Hitler's birthday. Brownlow says he had been struggling with writing the dialogue of the Nazi collaborators and so asked one of the men how they could justify the camps and the other horrors of the Reich. The self-confident, straightforward manner of the answer he got, making clear his racial justifications for the slaughter, shocked him; 'I was shattered' he says of the experience. Brownlow began to think that the best way to show the 'sick' nature of these beliefs was to let the adherents 'condemn themselves out of their own mouths'. It would also add to Brownlow and Mollo's aesthetic commitment to authenticity.

"The scene in question was cut from the film by its distributors United Artists and was only restored for its first domestic release in 1994."

(Because of that scene, the UK's Official Jews of the time didn't "get it" and called for this resolutely anti-Nazi film to be banned.)

But It Happened Here is still a highly watchable curio, and an astonishing accomplishment for two young men barely out of their teens. (Brownlow grew up to become a beloved expert on, and preservationist of, silent films, and Mollo is the man Hollywood calls in to consult on period military uniforms. His late brother John won an Oscar for his Star Wars costumes. Speaking of which, the cinematographer, Peter Suschitzky, went on to shoot The Empire Strikes Back — and The Rocky Horror Picture Show — among others.)

Today we see that England may have defeated the Nazis but has voluntarily adopted fascism regardless. As I used to quip frequently at my old blog when posting about the latest UK crackdown on free speech: "Come back, Luftwaffe! All is forgiven!"

George Orwell, normally a canny observer of his countrymen, confidently declared that goose-stepping would never catch on in Britain because "the people in the street would laugh." Except his nation has more or less outlawed laughing now, so there's that.

Back when laughing was still legal, the most famous episode of Fawlty Towers had German tourists come to stay at the hotel, prompting John Cleese's innkeeper to frantically order his staff: "Whatever you do, don't mention the war!"

Naturally, he's the one who can't hold his tongue. After imitating Hitler then shouting, "You invaded Poland!" Basil Fawlty suffers a breakdown.

"Don't mention the war" remains a popular catchphrase decades later, but the episode's last line always seemed more acute, mostly because the script gives a German the last word:

"How ever did they win?"

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one.