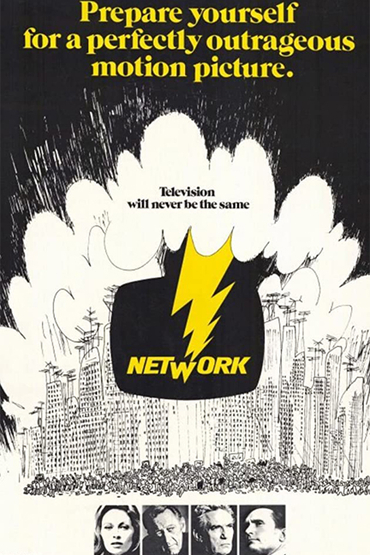

In one of my first columns, I asked, "What's left to say about Psycho?" The same could be asked about Network (1976).

I was 12 when Network came out, so I had no desire to see it in its original run, being at the time completely obsessed with the more pre-teen friendly Jaws (to the point of keeping a scrapbook that I hope I've thrown away.)

I'm not sure when I first watched Network from start to finish, but I do know when I got sick of any mention of it:

Some will recall the Great Glenn Beck Moral Panic of 2009 — all those tedious, tendentious "think pieces" claiming that Beck's (and Rush Limbaugh's and Alex Jones') rise had been foreshadowed by Network (and, once they'd drained that particular metaphorical motherlode, 1957's A Face in the Crowd.)

A now-defunct online publication hired me to puncture such theses. Writing about Network became such "net work" that I wished it had never been made.

This month, TCM aired Network multiple times. My husband had never seen it in full — I imagine this is a commonplace — so one night I left it on. I half-hoped the film would be overrated and dated, but it wasn't.

However, I did notice something for the first time. I took to Facebook to ask others if I was crazy, but my friends said that they, too, had never noticed this thing either, about this 44-year-old movie.

But first, a synopsis (although Network is so ubiquitous I feel silly even writing this.)

A veteran news anchor at the fictional UBS TV network, Howard Beale (Peter Finch), announces during his newscast that he is going to commit suicide, live on air, a week from that night. A clash (and later an affair) develops between craggy news producer Max Schumacher (William Holden) and younger, high-strung and ruthless broadcasting consultant Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), who wants to turn Beale's insanity into a show of its own. She gets her way, and this bizarre program becomes a cultural phenomenon and a ratings (and therefore, commercial sales) bonanza.

Surely we've all seen this clip dozens of times.

Paddy Chayefsky's Oscar-winning screenplay, among the top ten ever filmed, was much laboured upon, as his archived papers reveal. In the same way that, when Terminator 2 came out, you could actually see (with a sensory satisfaction I've rarely savored before or since) every single cent of its then-record $100 million budget onscreen, you can feel Chayefsky's hard work here, but — and this is key — you are not distracted by it. You enjoy a simmering, simpatico sense of profound appreciation for his craftsmanship every second of Network's running time, while simultaneously remaining deeply immersed in the world he's created.

In this sense, Network is quite like a cathedral: People MADE this, you think, but it is "this," and not those artisans, which is the actual point. This rare and precarious balance inspires awe. It is what Art is.

But then you're me, and you notice something.

Here's another clip from The Howard Beale Show, and remember that this is the highest rated show in Network's alternative America, and has at this point been on the air for weeks.

Did you hear it?

Howard Beale swore on television. Repeatedly. In 1976.

In 1976, you couldn't say "cancer" on American network television without sparking a national crisis, let alone "goddamn" or worse.

Yet confusingly, during one rant about the phoniness of the same medium that serves as his podium, Beale thunders that, "nobody ever gets cancer in Archie Bunker's house." This briefly breaks the movie's spell, because Chayefsky surely knew better: Edith Bunker's breast cancer scare — the seed of the aforementioned freak out — was a 1973 storyline on All in the Family.

While I'm at it, another spell-breaker: Marlene Warfield as Laureen Hobbs, the self-described "bad-ass Commie nigger." Her line readings are sometimes off, stressing the wrong syllables; I can't decide whether it is Warfield or her character — a revolutionary has been thrown into the foreign world of entertainment high finance — who find it hard to wrap their mouths around these lines, but her split-second stumbles are speed bumps in an otherwise impeccable scene.

They really should have cast Pam Grier.

But back to the swearing: In the universe of Network, the UBS Standards & Practices boys either do not exist or are not doing their jobs. Yes, Beale's show is live, but there was (and still is) a seven-second delay across the industry, to give them time to push their mute buttons (over which their real-life counterparts were particularly poised during that era's iteration of Saturday Night Live.)

Comedian George Carlin's 1972 "Seven Words You Can't Say on Television" routine was, by the time of Network's release, a touchstone of American culture. Even children (at least, those whose parents and older siblings bought comedy albums) could recite it by heart in the schoolyard.

(The fact that this routine was, like 99% of every "fact" concocted by leftists, based on almost-nonsense should surprise no one, although that paradoxical story in and of itself might make, well, a decent movie, were the means of production in our hands and not our enemies'.)

And where the hell is the FCC? As late as 2004, a Super Bowl half-time show "nip slip" earned CBS a five-figure fine from those stodgy watchdogs.

I searched Chayefsky's script for "FCC," and found this:

CHANEY

I don't care how bankrupt! You

can't seriously be proposing and

the rest of us seriously consider-

ing putting on a pornographic

network news show! The FCC will

kill us!

HACKETT

Sit down, Nelson. The FCC can't

do anything except rap our knuckles.

That's it.

In an era when petitions demanding the cancellation of television shows (like All in the Family) were as commonplace as strikes and hijackings, there is also no reference in the screenplay to some "citizens for decency" group lobbying for The Howard Beale Show to be pulled off the air.

Chayefsky made no attempt, however ridiculous, to explain why these ubiquitous petitioners, and the FCC, and Standards & Practices, are all missing in action. Neither is Network presented as an "alternative history" or other species of speculative fiction; in such genres, authors are expected to disclose, even briefly, how the Axis won World War II or JFK survived assassination, before getting on with the story.

In short, The Howard Beale Show could never have existed (for more than one episode, at the very most) in the 1970s, any more than a musical called Springtime for Hitler could strike dumb audience members with ticket stubs in their pockets with the words "Springtime for Hitler" printed right on them.

And yet, while I've been complaining about The Producers for a really long time, it took me my entire adult life to notice this massive hole in Network's fuselage.

How does a movie with a premise this impossible become so accurately prophetic?

(While I still don't buy the "Network = Glenn Beck" thesis, no one can deny that television, including its news departments, has indeed become almost as crass and sensational as anything on The Howard Beale Show.)

What a testament to the magicianship of Paddy Chayefsky (and, I'll reluctantly add, director Sidney Lumet, who has never been less "eat your liberal spinach" than here, to the point where I wonder if he really directed Network at all.)

But I still need to think about this a bit more (and also investigate whether or not 1981's Scanners was David Cronenberg's "answer film" to Network — note among other things the cut crystal physiognomy of the female fulcrums in both movies.)

Yes, I feel conned, and nobody likes feeling conned. (Which is why such crimes are underreported.)

And yet, what is Chartres but a sleight of hand monument to Air and to Heaven, fashioned out of the least likely elements: Stone and Earth?

Do we feel conned by a cathedral?

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one.