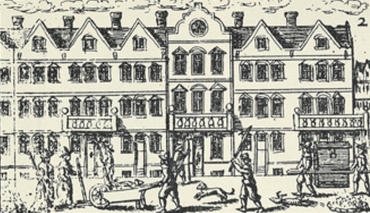

Welcome to Part Twenty-Three of my serialization of A Journal of the Plague Year, the latest in our series of audio adventures, Tales for Our Time. Daniel Defoe's enduring classic was first published in 1722, but in the form of a contemporary account of events half-a-century earlier - the Great Plague of London. CrossBorderGal, a Mark Steyn Club member with a nom de laptop far harder to live up to than it was in February, writes of Friday's installment:

Good sense argued in this episode (i.e., sheltering the apparently well away from those already stricken, instead of shutting them all up together). Wish we could have handled the current pandemic that way instead of closing the doors to almost everything for everybody.

Quite so, CBG. In tonight's episode, we explore in more detail the public administration of 1665 - which, compared with one that handcuffs you for taking a stroll in a park or fines you $500 for being parked in a church parking lot, sounds remarkably sane:

The vigilance of the magistrates was now put to the utmost trial—and, it must be confessed, can never be enough acknowledged on this occasion also...

They could never have forced the sick people out of their beds and out of their dwellings. It must not have been my Lord Mayor's officers, but an army of officers, that must have attempted it; and the people, on the other hand, would have been enraged and desperate, and would have killed those that should have offered to have meddled with them or with their children and relations, whatever had befallen them for it; so that they would have made the people, who, as it was, were in the most terrible distraction imaginable, I say, they would have made them stark mad; whereas the magistrates found it proper on several accounts to treat them with lenity and compassion, and not with violence and terror, such as dragging the sick out of their houses or obliging them to remove themselves, would have been.

Indeed. It is a paradox of the pre-democratic age that their rulers were often more mindful of the masses' sensibilities precisely because there was no peaceful way by which they might express their opinions. Judging by the ever more openly authoritarian carry-on by our present rulers, they seem pretty confident that, as George Orwell remarked in another context, "There is no turbulence left in England."

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear Part Twenty-Three of our adventure simply by clicking here and logging-in.

Earlier episodes can be found here - and if you've only joined our club in recent days and missed our earlier serials (Conan Doyle's The Tragedy of the Korosko, H G Wells' The Time Machine, Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent, Anthony Hope's The Prisoner of Zenda, plus Kipling, Dickens, Gogol, Kafka, Baroness Orczy, Jack London, Louisa May Alcott, John Buchan, L M Montgomery, Scott Fitzgerald, Victor Hugo and more), you can find them all here in an easily accessible Netflix-style tile format.

If you have friends who might appreciate Tales for Our Time, we have a special Steyn Club Gift Membership that lets them in on that and all the other fun in The Mark Steyn Club. To become a member of the Steyn Club, please click here - and please join me tomorrow for Part Twenty-Four of A Journal of the Plague Year.