There's too much chatter about movies that are "so bad, they're good." These admittedly amusing musings distract from a truly insidious phenomenon:

Movies "so good, they're bad."

No such creature as "just a movie" exists. We may (believe ourselves to) be capable of separating fact from fiction, but millions of people never will.

Take the "Hitler's Pope" canard. It was popularized by, of all things, a Soviet-orchestrated stage play called The Deputy, back in 1963. How many individuals have heard of this play, let alone seen it performed? A few thousand? Yet the Vatican's supposed collusion with the Nazis is widely considered "common knowledge," despite all the well-researched critiques which have not, in like fashion, been rendered down into easily digestible, entertaining, two-hour public performances.

I remain perturbed by Ben Affleck's reduction of Canada's crucial role in the rescue of American hostages in Argo. Brits object, among other things, to the portrayal of their ancestors as war criminals in The Patriot. James Cameron had to apologize for slandering a Titanic officer. Do not get me started on Thirteen Days...

And it gives me no (okay, a little...) pleasure to inform those of you forced to sit through corporate "team building" exercises based on the "square peg in a round hole" scene in Apollo 13 that, in actuality, one man came up with that lifesaving fix; as in most situations here on planet Earth, a team probably would have taken much longer and just screwed things up.

These weighty, slickly produced "historical" films, which earned hundreds of millions of dollars, varying degrees of critical acclaim, and numerous honors, are "so good, they're bad," one and all.

Their cynical "dramatic license" libels men and warps minds.

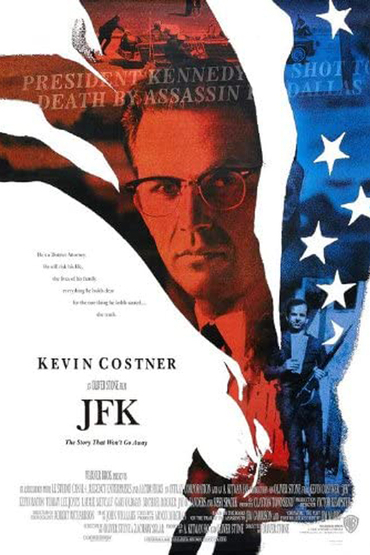

Which brings us to Oliver Stone's malignant opus, JFK (1991).

I only bring it up because Bob Dylan recently released his first original song in eight years, "Murder Most Foul," a 17-minute meditation upon the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Rolling Stone greeted it with unhinged enthusiasm, and the song became Dylan's first ever number one hit.

I'm sure many of these listeners will pass their quarantine time digging into Dylan's lyrics about "three hobos" and the "grassy knoll."

Sure, a few might trip over JFKLancer.com, the preeminent conspiracy buff website, but they'll likely be overwhelmed by the sheer muchness of it all.

What worries me is that most will satisfy their curiosity by watching JFK.

Norman Mailer called JFK "the worst great movie ever made" — and he liked it. He was right, but for the wrong reasons.

Mailer takes issue with Stone's "crude" style, whatever that means. It certainly isn't on display in this Best Picture nominee's (dangerously) seductive cinematography and editing, which won well-deserved Academy Awards.

The multiple problems with JFK as History, as Truth — and this is how Stone viewed the film, and wanted others to — were raised at length (and in depth) even before the film's release, but the average viewer today is probably unaware of these 30-year-old debates.

My complaints begin with the title:

It should have been called Garrison, after the film's "hero." A New Orleans D.A., Jim Garrison tried and failed, in 1967, to convict some admittedly sleazy-seeming locals of being part of the "conspiracy" to assassinate Kennedy, which he theorized had been — and I can't believe I'm forced to type this — a "homosexual thrill killing."

Stone, and actor Kevin Costner, portray Jim Garrison as a real-life Atticus Finch, when, in reality, "[o]n the job, he was accused of using truth serums, bribing witnesses, and making promises for reduced sentences," and "was not present at much of the trial."

These are just my beefs with the title and the main character, and the damn thing is three and a half hours long. This fellow has compiled an extensive list of Stone's JFK prestidigitations; while it isn't as well sourced as I'd like, I must share my favorite:

In the film, the rifle of one of the "grassy knoll" shooters emits a cloud of smoke, but, "Stone could find no gun that emitted that much smoke, [so he] had [a] special effects man blow smoke from bellows."

The author adds:

"Many consider this an appropriate metaphor for the entire movie."

Or perhaps it isn't necessary to visit such a website to learn how mendacious JFK is. A moment's googling reveals that modern technology has since torpedoed such "evidence" of conspiracy as the "doctored" "backyard photo" of assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, and the Dallas motorcycle cop's dictabelt audio long-alleged to have recorded a fourth shot.

Those seven wounds received by two men struck by a single, apparently "zigzagging" cartridge — the Commission's widely mocked "magic bullet theory" — is demonstrated in JFK almost as comic relief.

However, it is easily explained:

In one segment [of this documentary], the producers showed the actual car in which the president and the others had been riding that day. One feature of the car, which I'd never heard or read about before, made my jaw literally drop. The back seat, where JFK rode, was three inches higher than the front seat, where Connally rode. Once that adjustment was made, the line from Oswald's rifle to Kennedy's upper back to Connally's ribcage and wrist appeared absolutely straight. There was no need for a magic bullet.

But what about the famous "Zapruder film" of the assassination, which has for over 50 years been considered the unassailable "time clock" of the murder, since a movie camera's frames-per-second rate is invariable?

This narrative was pushed by Time, Inc., which owned LIFE magazine, as well as the exclusive rights to that grim, gory footage. LIFE, by far the most widely read magazine of its era, printed select frames, with captions, thereby establishing the narrative that three bullets were fired at the motorcade in six seconds.

This rightly struck many as a less-than-believable feat of marksmanship, and thus the conspiracy theory industry was born (midwifed, by the way, by our old friends, the Russians, as we've only recently found out.)

Already traumatized by the assassination itself (which Don DeLillo has called "the seven seconds that broke the back of the American century"), the nation's psyche was poisoned by all this conspiracy-driven paranoia; movie violence became more prevalent; and, not incidentally, Dan Rather made his name.

The trouble, however, is that Abraham Zapruder had stopped and re-started his movie camera as the motorcade approached, leaving many seconds unrecorded. This has never been a secret, but neither did anyone seem to care. Buffs were so invested in the presumption that the footage he did shoot showed the assassination in full that they laboured to the point of absurdity (shooters under manhole covers, even in the Secret Service follow-up car) to squeeze their "facts" into the tiny frames of Zapruder's film.

The Warren Commission was no better. Eyewitness testimony and other evidence was discarded if it didn't match up with this blurry, happenstance strip of silent, amateur footage. Hadn't LIFE pronounced that, "Of all the witnesses to the tragedy, the only unimpeachable one is the eight-millimeter movie camera of Abraham Zapruder."

After all, the camera never lies, right?

It wasn't until 2004 that one Max Holland raised an objection so simple, so obvious it's frankly embarrassing:

"If one discards the notion that Zapruder recorded the shooting sequence in full, it has the virtue of solving several puzzles that have consistently defied explanation."

He presents compelling evidence that the first shot was fired while Zapruder had his camera turned off. Firing off two more shots instead of three now becomes eminently doable in those crucial six seconds. With that, five decade's worth of spurious "evidential" dominos tumble in turn.

"And why has it taken so long to realize that the assassination and the Zapruder film are not one and the same?" Holland asks. "Part of the answer lies in the power of the film itself.

"As the critic Richard B. Woodward wrote in The Times in 2003, the assassination became "[the first event of international importance to have] fused with one representation, so much so that Kennedy's death is virtually unimaginable without Zapruder's film."

So don't try to tell me that movies "don't matter."

Ironically, the only blameless character in this world-historical Centralia is the humble Dallas schmata manufacturer who hurried down to Dealey Plaza on his lunch hour to take some home movies of his president:

Abraham Zapruder himself.

The same cannot be said for Oliver Stone.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, sign up for a membership for yourself or a loved one. Meet your fellow Mark Steyn Club members by joining Mark, Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and other special guests aboard our upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise down the Mediterranean.