Here's the 13th episode of our current Tale for Our Time, Daniel Defoe's vivid and journalistic Journal of the Plague Year.

Tonight's episode of our story invites the usual comparisons with April 2020. In Lombardy and elsewhere in Italy, the cemeteries and crematoria are full, and bodies are stacked in military trucks to be driven south to less congested resting places. Defoe would not have been surprised:

It is to be noted here that the dead-carts in the city were not confined to particular parishes, but one cart went through several parishes, according as the number of dead presented; nor were they tied to carry the dead to their respective parishes, but many of the dead taken up in the city were carried to the burying-ground in the out-parts for want of room.

Nor would Defoe have been surprised by the lack of preparation for obvious consequences - such as "relief of the poor" - although the inertia of the bloated bureaucracy of 2020 does not compare well with the relative efficiency of its slimmed down seventeenth-century predecessor, which, without benefit of wiring and direct deposit, would have been able to get $1,200 checks to the citizenry within a fortnight. Nevertheless:

Surely never city, at least of this bulk and magnitude, was taken in a condition so perfectly unprepared for such a dreadful visitation, whether I am to speak of the civil preparations or religious. They were, indeed, as if they had had no warning, no expectation, no apprehensions, and consequently the least provision imaginable was made for it in a public way. For example, the Lord Mayor and sheriffs had made no provision as magistrates for the regulations which were to be observed. They had gone into no measures for relief of the poor. The citizens had no public magazines or storehouses for corn or meal for the subsistence of the poor, which if they had provided themselves, as in such cases is done abroad, many miserable families who were now reduced to the utmost distress would have been relieved, and that in a better manner than now could be done.

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear me read Part 13 of A Journal of the Plague Year simply by clicking here and logging-in. Earlier episodes can be found here.

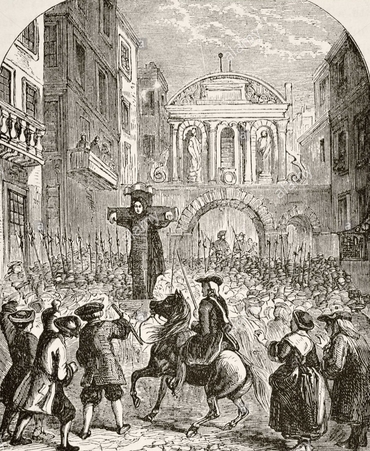

We made rather light of Defoe's time in the pillory yesterday, but as Owen Morgan, a First Week Founding Member of the Steyn Club from Hampshire (old, not New), reminds us:

Sentencing someone to the pillory was a way of inflicting at least a potential death sentence, but without issuing such a sentence formally. Defoe, probably, was not meant to come out alive. Although the stocks and the pillory tend to be confused (and I don't suppose that being confined to the stocks was altogether pleasant), the pillory differed in exposing the head of the prisoner to anything thrown at him or, quite often, her. With the hands and arms prevented from warding off stones, clubs, or anything else, the prisoner was defenceless against a hostile crowd.

Defoe was popular and faced no such mob.

Still, you've got to be a pretty cool customer to carry that off.

If you've yet to hear any of our Tales for Our Time, you can do so by joining The Mark Steyn Club. For more details, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership. I'll be hosting Part 14 of A Journal of the Plague Year right here tomorrow evening, and just ahead of that, on Friday morning, I'll be back with our latest audio Coronacopia on The Mark Steyn Show.