Just ahead of our current Tale for Our Time - Daniel Defoe's vivid and enduring Journal of the Plague Year - let me put in a word for our complementary entertainment at the other end of the day: the new socially-distanced audio-only Mark Steyn Show. I'm delighted that some folks (if not all) are enjoying both. Ian Wilson, an Ontario member of The Mark Steyn Club, writes:

Hi Mark, thank you for this new format. I listen to your show by day and then the family gathers around each evening to listen to a couple of your episodes of Tales. A throwback to pre-television days.

Very cozy, Ian. Think I'll get the pipe and slippers and a mug of Ovaltine. Our morning and evening shows (North American time) are the same story three-and-a-half centuries apart: If you heard Defoe's account of the dead-cart doing its work after dark the other night, you will not have been surprised by the horrifying pictures in today's papers of bodies being loaded by forklift into refrigerated trucks in the small hours outside New York hospitals.

In tonight's episode, our narrator offers a few observations he hopes may come in useful for those who may see "the like dreadful visitation" in their own towns:

(1) The infection generally came into the houses of the citizens by the means of their servants, whom they were obliged to send up and down the streets for necessaries; that is to say, for food or physic, to bakehouses, brew-houses, shops, &c.; and who going necessarily through the streets into shops, markets, and the like, it was impossible but that they should, one way or other, meet with distempered people, who conveyed the fatal breath into them, and they brought it home to the families to which they belonged.

That is true, then as now, which is why persons who are already de facto quarantined and would thus be assumed to be at lower risk - such as the inmates of old folks' homes - are in fact especially vulnerable: their carers are coming and going and walking infections in and out to those who cannot themselves leave.

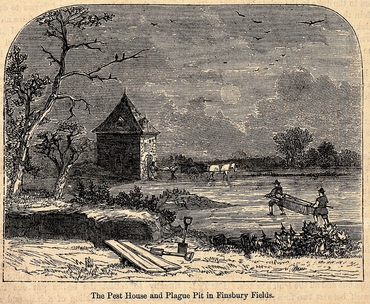

(2) It was a great mistake that such a great city as this had but one pest-house; for had there been, instead of one pest-house—viz., beyond Bunhill Fields, where, at most, they could receive, perhaps, two hundred or three hundred people—I say, had there, instead of that one, been several pest-houses, every one able to contain a thousand people, without lying two in a bed, or two beds in a room... I am persuaded, and was all the while of that opinion, that not so many, by several thousands, had died.

The situation of New York, where the Javits Center has been turned into a makeshift hospital, seems relevant in this respect. On 9/11, "the day the world changed", the city's doctors and nurses awaited patients who never came - because, for the most part, you either got out of the buildings and were okay, or you didn't and were dead. But there were not a lot of injured in between those categories. Nevertheless, understanding that the city was one of the world's biggest targets, government at all levels has spent a fortune on supposed disaster preparedness for New York - and right now there's not a lot of evidence of where those dollars have gone.

(3) This put it out of question to me, that the calamity was spread by infection; that is to say, by some certain steams or fumes, which the physicians call effluvia, by the breath, or by the sweat, or by the stench of the sores of the sick persons, or some other way, perhaps, beyond even the reach of the physicians themselves, which effluvia affected the sound who came within certain distances of the sick, immediately penetrating the vital parts of the said sound persons, putting their blood into an immediate ferment, and agitating their spirits to that degree which it was found they were agitated; and so those newly infected persons communicated it in the same manner to others.

The airborne infection from the choir rehearsal I mentioned on this morning's show would have rung very familiar to Defoe.

I must here take further notice that nothing was more fatal to the inhabitants of this city than the supine negligence of the people themselves, who, during the long notice or warning they had of the visitation, made no provision for it by laying in store of provisions, or of other necessaries, by which they might have lived retired and within their own houses.

Switzerland seems the model here. The Swiss Government both stockpiles for the nation and encourages its citizens to do so as well. But, as I side, throughout this journal from 1665 you will find all kinds of pre-echoes of 2020.

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear this latest installment of our tale simply by clicking here and logging-in.

You can enjoy A Journal of the Plague Year episode by episode, night by night, twenty minutes before you lower your lamp. Or, alternatively, do feel free to binge-listen: you can find all the earlier instalments here.

If you've yet to hear any of our first thirty-five Tales for Our Time, you can do so by joining The Mark Steyn Club. Or, if you need an extra-special present for someone, why not give your loved one a Gift Membership and start him or her off with three dozen or so cracking yarns? And do join us tomorrow for another episode of this Daniel Defoe classic.