Martin Scorsese hasn't been entirely truthful with us.

With last year's The Irishman, the director took needless liberties with an already compelling true story.

Michael Franzese agrees, and he should know. The former NYC Mafia capo's new vocation? Fact-checking classic mobster movies on YouTube.

"I don't really think he looks like me," Franzese deadpans about the actor who, for about two seconds, "plays" him in Scorsese's Goodfellas.

The ex-con also punctures a famous scene in the same film that he says he's "been asked about a million times."

Sadly, no: imprisoned Mafiosi were never allowed to cook their own red sauce.

(As fun as Franzese's videos are, fact-checking Mafia movies is somewhat beside the point: Mario Puzo made up a lot of the cosa nostra mythology in The Godfather — and the real Mafia liked these "traditions" so much, they adopted them.)

Anyway, despite these and other fabrications on the director's part, Franzese admires Scorsese's work, and rightly so.

(Even if I didn't think that already, do you think I'd disagree with this guy?)

When Martin Scorsese isn't making movies, he's restoring and preserving other people's, but even then, he can't resist the urge to embellish.

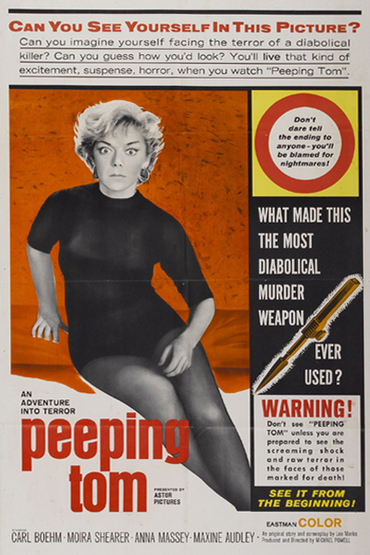

In 1979, Scorsese oversaw the restoration of 1960's Peeping Tom, directed by one of his heroes, Michael Powell (Black Narcissus, The Thief of Bagdad, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp.)

Then, in 2010, he championed its rehabilitation with a series of highly publicized and popular screenings, coinciding with the movie's 50th anniversary.

Peeping Tom centers on amateur filmmaker Mark Lewis (Austrian actor Carl Boehm, at turns alien and ordinary.) By day, he's a handsome, soft-spoken movie studio focus puller and part-time pin-up photographer. By night, Mark films the reactions of women he murders by way of "the spiked leg of a tripod attached to his 16mm camera, upon which he has also mounted a mirror so that his victims are forced to watch their own contorted faces as they expire."

During the restoration's publicity jaunt, the press and film buffs alike hoovered up Scorsese's tantalizing Peeping Tom backstory – that this widely-condemned and long-forgotten serial killer movie destroyed Powell's otherwise magisterial career. A case of Frankenstein's monster slaughtering his creator, a genius ahead of his time.

Worse (the saga continued), Hitchcock's superficially similar Psycho was released that same year, to big box office returns and enduring critical regard.

This irony-rich elevator pitch taps into so many archetypes (along with the vanities of its audience: a cognoscenti always craving a "new" "misunderstood" artist to "discover") it's no wonder it became received wisdom.

(Far from incidentally, Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese's peerless editor-for-life, also happens to be Powell's devoted widow.)

The truth, however, is murkier:

While Peeping Tom was certainly denounced upon release to a degree rarely witnessed before or since — "The only really satisfactory way to dispose of Peeping Tom would be to shovel it up and flush it swiftly down the nearest sewer" is only the most famous of similar reviews — the legend elides the fact that Powell's previous five films had bombed too.

It didn't help that Peeping Tom was a sharp swerve away from the more elevated themes and sophisticated, magical productions, like The Red Shoes, that everyone had come to expect, and demand, from Powell. Imagine if Merchant Ivory came out with a grindhouse slasher film, except that slasher films didn't even exist when they did so.

Because that was the case with Peeping Tom: viewers were unaccustomed to its brazen, Eastmancolor brutality — and possibly insulted by the movie's implication that by watching this (or any) film, we are all voyeurs like Mark, complicit (however unintentionally) in turning other people into objects, and crime into entertainment.

A neurotic introvert, Mark only feels comfortable when viewing the world (especially the world of women) through a glass lens. Behind the shield of his camera, this socially shaky man-boy becomes authoritative, confident enough even to kill.

Powell places us behind the camera too, in POV shots, forcing us to confront our own culpability.

(As I've noted before, this bite-the-hand-that-feeds-you challenge to paying customers helped doom another failure-turned-classic, Ace in the Hole.)

Why do we happily give over our money or time to be voluntarily frightened and titillated by images on screens large and small, all the while gleefully booing the villain whose evil actions we've paid to watch?

Certain tribesmen of pop anthropology fame feared that photography stole their souls. We may mock their superstitions, but manufactured images — of impossibly perfect fashion models, Instagrammed homes and vacations, hardcore sexual acts, violence real and imaginary — can have a corrosive impact on us all, not just weirdos like Mark.

Quantum physics declares that objects are transformed simply by being observed. But what of us, the observers?

We needn't invoke 21st century physics: What did Jesus say about the man who looks at a woman with lust?

When it was rereleased by Scorsese & co. on its 50th anniversary, Peeping Tom was widely hailed as perhaps the ultimate "movie about movies".

Powell made an occasionally clumsy but laudable attempt to autopsy the very act of seeing itself – the relationship between movie maker and audience, as well as what had been dubbed, back in 1975, "the male gaze."

(The critic who coined that phrase, Laura Mulvey, recorded the commentary track for the film's Criterion edition. That her now-famous feminist film theory had first been introduced into popular consciousness a few years earlier, by a man, is a topic for another day.)

As Peeping Tom's 60th anniversary approaches, the movie prompts other meditations:

Some will immediately recognize the main character as an "incel." Was that a word we didn't need in 2010 — or 1960? Or just one we didn't know we did?

Mark calls the private snuff film he's piecing together at night "a documentary;" at a time when most Englishmen (and many Americans) didn't even own a TV, he carries around a camera the size of one's head, and often attempts, awkwardly, to conceal it from quizzical stares.

How many people have you seen, today alone, capturing images of themselves and others on their tiny phones, without shame or effort, each convinced that their visions are worthy of preservation? We are all documentarians — and broadcasters and podcasters and publishers — now, or can be, with little financial outlay or other barriers to entry, including the approbation of those around us.

And if our pictures don't come out perfectly, there's always Photoshop or Perfect365.

Privacy? What's that? Mark's paraphilic fetish is now vanilla.

Millions of children and young adults have no experience of a world devoid of ubiquitous lenses and screens. "Pix or it didn't happen" as those kids say — or used to. (The phrase congealed into cliché at a revealingly rapid rate.)

News of criminals matter-of-factly recording and even uploading their crimes is no longer novel. Last year, "a Japanese man was charged with assault after using Instagram to take his stalking of a woman from the internet onto the streets (...) the man ascertained the woman's location by looking at the 'reflection in her eyes' on her Instagram selfies."

We learn that, as a child, Peeping Tom's Mark was a guinea pig in the name of "science":

His researcher father used him as the subject of experiments in fear, recording the boy's tearful, terrified reactions when, for instance, his father tosses a lizard onto his bed.

These scenes were what really shocked to Peeping Tom's audiences in 1960, more so than the bloodless, just-off-camera murders. Who would subject their child to such cruelty?

Have you managed to get this far into today without reading about a child "drag queen" or one who's "transitioning"? Or of another, whose obsession with the "science" of "climate change" has resulted in both suicidal self-harm and international acclaim? Maybe you caught a "hilarious" viral video of children being "pranked" over pilfered Halloween candy, and reduced to tears?

Or, closer to home, you overheard another parent boast about their plans to put their now-toddler daughters on the Pill at an "appropriate" age?

And finally:

Have you seen, or heard about, a new movie or TV show that "everyone" hates? It's coarse and weird and gross and "not even funny." Whoever made it should be ashamed of themselves. What's the world coming to?

Did you pause to wonder if, in 50 or 60 years, our descendants might point to this creation and sigh, "How could people not 'get' it? Why didn't they see it as a warning?"

That said, in Peeping Tom, the only person who sees through Mark — and then, only through a glass, darkly — is blind.

(Peeping Tom can be watched for free here.)

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one. To meet many of your fellow club members in person, join Mark along with Conrad Black, Michele Bachmann and several others aboard our upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise down the Mediterranean.