Parasite recently became the first foreign film to win the Oscar for Best Picture.

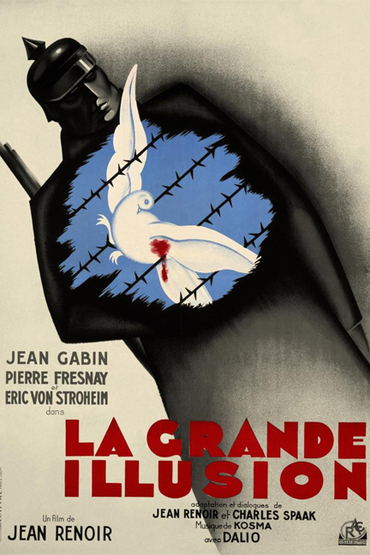

The first foreign film ever nominated in that category, however, was Jean Renoir's Grand Illusion (1937).

I can't speak to whether or not Parasite deserved its prize, but Grand Illusion's reputation as one of the glories of cinema has only grown, even though it was essentially a "lost film" for generations.

Fascists across Europe set out to destroy every print; a stashed negative was discovered in Moscow and "returned to France in the 1960s, but sat unidentified in storage in Toulouse Cinémathèque for over 30 years." (A state of affairs that will surprise no one who has ever had the misfortune of "working" with individuals of Gallic ancestry...)

Certainly, the film it lost the Academy Award to — Capra's You Can't Take It With You — hasn't aged particularly well. (An all-too-common occurrence.)

But has Grand Illusion?

Grand Illusion mostly takes place within German-run prisoner of war camps during World War I, from which French officers from different backgrounds plot to escape:

Arch aristocrat Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay), craggy working-class Lieutenant Maréchal (Jean Gabin), and amiable Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), the scion of a nouveau riche Jewish banking family.

Throughout, their German nemesis (although that isn't quite the right word) is Rittmeister von Rauffenstein (Renoir's personal hero, Erich von Stroheim), the aristocratic aviator who shot down Boeldieu and Maréchal, then serves as their commandant when the prisoners are transferred to an "escape proof" castle keep.

Filmed in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, with World War II looming, Renoir used the story and setting to test and tease out his own Popular Front ideals, particularly that class was (or at least should be) a more sensible force for group loyalty than nationality. "Workers of the world, unite" and all that.

In the hands of anyone other than the son (and reluctant model) of one of the finest 19th century painters, Grand Illusion could have easily been a deservedly forgotten propaganda film. To his credit, Renoir resisted the temptation (despite the depth of his convictions and the pressure of crushing world-historical events) to squeeze out some "edgy" satirical agitprop.

Instead, his polestar here is the least Leftist dogma imaginable:

The professional soldier's code, that officers of all countries are "equals." This is cleverly illustrated at film's very start: The French officers' mess is the mirror image of the German one, right down to the bartender and gramophone. These are enemies who share not just rank, but tastes, and even acquaintances, across national borders.

Or used to: The presence of non-aristocratic officers like Maréchal and Rosenthal in this new kind of war allows Renoir to candidly explore class fissures and other bigotries, and the chasm between rarefied theory and quotidian practice.

Rauffenstein, rigidly adhering to the code (literally: von Stroheim came up with his character's stifling neck brace) treats all three captured fellow officers with florid courtesy — in public.

But alone with Boeldieu, he confesses his inability to accept commoners as officers, and his dread that the old order that the two men have devoted their lives to preserving is nevertheless facing extinction.

Likewise, in a moment of supreme stress, Maréchal yells at Rosenthal, "I never liked Jews." And the prisoners snub a perfectly decent fellow officer who happens to be black, even though he's supposedly as French as they are. (So much for that "revolution," Rauffenstein...)

But these fractures are not the norm. Everyone is generally trying to do their best, and then some, under strained circumstances, motivated either by duty or decency.

While some may cringe at Renoir's blatant depiction of "good German" Rauffenstein, or (possibly worse in French eyes) "good Jew" Rosenthal, such portrayals were inspired (and controversial) for their time. In fact, it's easy to imagine Rauffenstein, should he live that long, taking part in the July Plot.

(Or not? Goebbels, who led the charge to eradicate every copy of the film, fumed that "no German officer is like" Rauffenstein, leading a French critic to quip, "Too bad for them.")

And with the Dreyfus Affair a matter of living memory, we can forgive in-your-face moments like Rosenthal's fond musings upon a nativity scene Jesus carved from a potato: "An ancestor of mine."

(I mean: it's true, but it may strike some viewers today as corny and, well, Forrest Gump-y — for which Renoir cannot be blamed.)

Now back to my original concern:

What hasn't "aged well" isn't Grand Illusion but the high-toned commentary about it, which gives the impression of ransom notes cut-and-pasted from copies of the same newspaper.

Grand Illusion, we are repeatedly informed, is one of the GREAT ANTI-WAR FILMS! An INDICTMENT! of MAN-MADE BORDERS! and other, well, ILLUSIONS!

The trouble is, Grand Illusion (particularly compared to, say, Paths of Glory or even puny Slaughterhouse 5) doesn't make war seem particularly dreadful.

Few shots are fired, and there are no battle scenes. Zero prisoners are hanged or tortured. Everybody gets their care packages — Rosenthal shares the ostentatiously gourmet ones from his wealthy family with unbounded delight — while the Germans slurp cabbage soup (again). Maréchal ends up in solitary for a time, but a kindly old German guard (who looks in worse shape than his captive) gives him cigarettes and a harmonica.

Now, I realize this makes me a very strange person, but when I was growing up, while other kids were fantasizing about living in the Brady family house, I imagined it would be more congenial to reside in Stalag 13. (Maybe you had to live with my family to fully understand the appeal of this alternative...)

Hogan's Heroes takes a lot of guff, but the prisoners in Grand Illusion are having just as a grand a time. (By the way: In a sub rosa gesture Renoir himself might have smiled upon, all the Nazis on Hogan's Heroes were deliberately played by Jewish actors.)

Again and again in Grand Illusion, we hear the French expression C'est la guerre which, in contrast to its American equivalent — "War is hell" — carries more than a whiff of resignation, and even approval.

And if war could be avoided simply by recalling our "common humanity," by becoming sophisticated internationalists — as so many of these film historians proclaim with almost audible sighs — then explain why Rauffenstein and Boeldieu (two high-culture polyglots who even wear identical monocles) are fighting on opposite sides.

Hell, didn't WWI start in the first place because all these fancy bigshots were related to each other?

So it pains me to say that, if Renoir set out to make an anti-war movie, he failed.

Critics also love to point out that GRAND ILLUSION IS THE TEMPLATE FOR EVERY PRISON CAMP MOVIE SINCE! but think about it:

There are only so many ways one can dig a tunnel and dispose of the dirt. It seems a curious thing to praise in an already praiseworthy film.

No ode to Grand Illusion is apparently considered exhaustive unless it also includes FDR's pronouncement that "everyone who believes in democracy should see this film." Because you should always accept movie recommendations from a long-dead dude who raised the price of gold by 21 cents because "it's a lucky number." The Battle of Algiers is a great movie too, but telling me "Malcolm X gave it a thumbs up" wouldn't exactly be a selling point.

In any event, ransom notes serve only one purpose: To compel obedience. Amusingly, having hailed Renoir's refusal to lecture his viewers, these critics are the ones doing the haranguing.

Again, my peculiar temperament may be the trouble here, but reading even the most eloquent hymns to Grand Illusion made me wonder, not for the first time in my life, whether or not we'd all watched the same picture.

I'm glad I didn't read any of these tributes before I hit the "play" button.

Grand Illusion is indeed a masterful and magisterial film. Renoir's "poetic realism" style is sublime, there are too many unforgettable scenes to list here, and the performances are exceptional. I promise it will haunt you for some time.

But a final complaint:

I remain puzzled by the commonplace descriptive of Jean Renoir as a "HUMANIST!" Too many individuals who've shared that once-fashionable appellation — Gandhi, H.G. Wells, Bertrand Russell — were decidedly "animalistic" in much of their conduct and prescriptions.

However, if by "humanist," they mean that Grand Illusion is more alive than many flesh and blood people you'll meet — including me, some of these days — then that adjective is utterly apt.

(Criterion Channel subscribers can view Grand Illusion until February 29. It is also available from iTunes.)