"The test of a first-rate intelligence," claimed F. Scott Fitzgerald, "is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function."

This concept is either perfectly illustrated or proven demonstrably false (depending upon your definitions of "first-rate" or "function") every year around this time, when the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame announces its latest inductees.

My friends and I, along with untold strangers, immediately take to our keyboards to declare, once again, that:

a) The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame has become an utter irrelevance, BUT...

b) its continued refusal to recognize certain artists in favor of less deserving (and decidedly non-"rock & roll") ones is a sin crying out to heaven for vengeance.

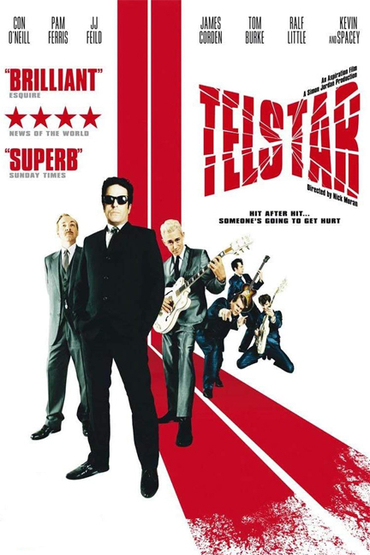

Surf guitarist Dick Dale's non-inclusion is a point of particular contention. Others champion Lonnie Donegan. But I am apparently alone in my insistence that the Hall at least nominate Joe Meek, subject of the 2008 biopic Telstar.

His name is unfamiliar to most Americans, but in England, Meek is a legend, a kind of combination Alan Turing, Phil Spector, Nicholas Tesla and Brian Epstein.

Meek was an eccentric of the species unique to the British isles: Think of the anorak'd trainspotter; the solitary tinkerers in their backyard sheds; the aristocratic flâneurs illustrated in the classic English Eccentrics, who wore birdcages for hats; or the less celebrated lower-middle class fellows you occasionally read about who've collected chamber pots since the age of eight.

We tend to play lip service to the existence of eccentrics. Don't they make society a more colorful place, and prick our conformist consciences? Yet in truth, eccentrics, like gorgeous but hostile uninhabitable planets, are best admired from a great distance.

Here on planet Earth, eccentrics, however brilliant — think of Glenn Gould or Keith Moon — tend to burden their friends, families and professional colleagues to a selfish, even sinful, degree.

And Joe Meek was one of these.

A country lad obsessed since childhood with phonographs and microphones, he was remembered by his more rugged, "outdoors" brothers as "an indoor boy." Joe repaired radios during his National Service, then landed sound engineering jobs in London.

It was the dawn of the 1960s, and Meek watched the rise of Larry Parnes (who was building a stable of pretty boy singers, re-baptising them Marty Wilde, Vince Eager and Dickie Pride) and Brian Epstein, a record shop proprietor with artist management ambitions.

That all three men were (necessarily closeted) gay men is a possible fluke I'll leave to others to ponder. In any event, Meek wanted to get in on this Svengali-esque impresario action, possibly (at least in part) for the same semi-sexual reasons.

But Meek had talents the other two did not: He'd be able to record his musicians, too. Using army surplus equipment, he set up a recording studio in a three-storey flat above a handbag shop, placing mics in every room, including the lavatory.

He gathered around himself a collection of enthusiastic young tea boys and all-around dogsbodies, and a far more reluctant but desperate house band, The Outlaws.

I should mention at this juncture that Joe Meek couldn't read music or play an instrument, and was by all accounts absolutely tone deaf.

Melodies came to him, often, he claimed, through the spirit of the late Buddy Holly, with whom he was obsessed. He'd yell out these tunes, and The Outlaws, or his house composer Geoff Goddard, were tasked with bringing them to life.

One such song was the Frankie Laine-ish "Johnny, Remember Me," a hit for The Outlaws and rising telly star John Leyton.

But while he worked with a hundred artists on records now mostly forgotten — actor Con O'Neill prepared for the role by listening "to everything [Meek] ever produced. And that's a week I'll never get back" — Meek acquired immortality through another "dream" song, an instrumental tribute to the new Telstar communications satellite performed by The Outlaws (now renamed The Tornados, with a new bleached blond bassist who went by his last name, Heinz.

Beating the Beatles to the punch, Telstar was the first record by a British band to hit #1 on the U.S. charts.

Meek fell into a common trap: The belief that from now on, like the satellite that inspired him, he had nowhere to go but up. Eventually, however, Telstar crashed down to earth, and so did Meek.

A French composer sued him over "Telstar," accusing Meek of stealing his song. Convinced he'd eventually win a huge settlement instead, Meek spent against this imaginary money, mostly to promote his new favorite, Heinz. (Telstar explicitly dramatizes a sexual relationship between Heinz and Meek, one the real Heinz denies.)

Next, Meek was arrested for "cottaging" during a routine raid by undercover police on public washrooms favored by cruising gay men. Disgraced and increasingly paranoid — it's likely he was self-medicating on street drugs to treat undiagnosed schizophrenia — Meek snapped and shot his landlady (this is portrayed as an accident in Telstar), then turned the gun on himself.

It was February 3, 1967, the anniversary of Buddy Holly's death.

Meek didn't live to see the Beatles and the other "British invasion" bands he loathed take over the world, pushing the quirky novelty songs he specialized in off the charts.

Meek thought he was writing for "the future;" atomic age aficionados praise his epic album I Hear a New World, which I find unlistenable. But as Charles Monagan writes, it was "a future that never was," of flying cars and colonies on the moon.

As for the movie Telstar, it is fast paced and entertaining, with a great performance by O'Neil, a distracting one by Kevin Spacey, and a delightful turn by James Corden, playing drummer Clem Cattini, who went on to play on 42 UK #1 singles. Justin Hawkins is a terrific Screaming Lord Sutch, who, come to think of it, deserves a spot in the Hall of Fame as well. Here's the real thing in action circa 1964.

The lip syncing in Telstar isn't the best, and whoever is supposed to be Gene Vincent has all the charisma of a rotten turnip.

More importantly, Telstar didn't spend as much time as it should on either Meek's childhood, or his DIY recording tricks; we see a lot of frantic knob-twirling but that's about it. I suggest watching Telstar before or after taking in this well-crafted BBC 4 Agenda documentary on his life.

Finally: I started working on this column on February 3. This is, I assure you, a total coincidence, but I doubt Meek would agree.

~Members of the Mark Steyn Club can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. Commenting privileges are among the many perks reserved exclusively for members of the club, so make sure to sign up for a membership to combat your fear of missing out. If you'd like to put faces to many of the names in the comment section, come out to our third annual cruise, which is coming up in October. This year, the Mark Steyn Cruise will set sail from Rome, with Michele Bachmann, John O'Sullivan and Douglas Murray among its special guests.