Last week I took a poke at the beloved leftist slogan, "Words can kill."

Yet it occurred to me later that many conservatives espouse a similar belief:

That, as Richard M. Weaver declared in his eponymous 1948 book, "ideas have consequences."

I'll leave it those smarter than I to crack this apparent paradox. I'm just the movie chick around here, so let's look at a film that explores such notions.

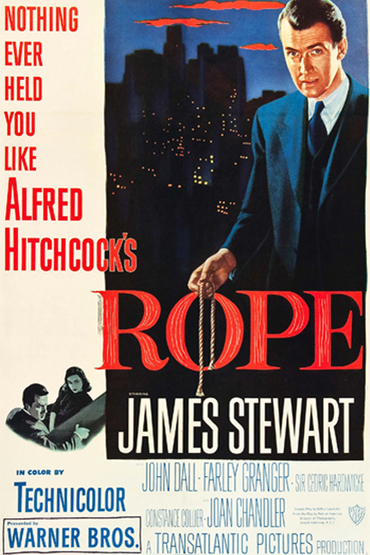

Released the same year as Weaver's masterwork, Alfred Hitchcock's Rope was long regarded as one of his lesser efforts, a mere gimmicky curio.

It's a film shot in what we're meant to understand is one long take, the better to recreate the experience of watching a stage play (which Rope originally was).

But that feat was unachievable in those days, when a Technicolor camera's film cartridges had to be replaced every ten minutes. Therefore, Hitchcock set himself a personal challenge: to employ the fewest cuts possible, defying his own creative instincts and putting aside his signature staccato technique.

Sure enough, the finished 80-minute movie contains only ten edits (traditional hard cuts plus not very subtle dissolves), a remarkable technical achievement under daunting conditions.

Still, Hitchcock later called Rope "an experiment that didn't work out."

It fell into legendary obscurity until a 1984 rerelease prompted critical re-evaluation and introduced the movie to new generations.

As Rope opens, three young male friends are gathered for cocktails in an enviable Manhattan apartment, when two of the pals strangle the third and cram his corpse into a decorative wooden chest.

Then they throw a party, arranging the refreshments on the trunk. The dead man's unknowing loved ones sip champagne and make arch small talk just inches from his cooling corpse.

As the minutes tick by, these guests become increasingly agitated by the dead man's "absence" — he was supposed to join them there.

Of all the partygoers, the murderers — supercilious Brandon (John Dall) and sensitive Philip (Farley Granger) — are especially fond of Rupert Cadell (Jimmy Stewart), who taught all three boys at prep school, feeding them underdone Nietzsche by the spoonful:

Intellectually superior people (like themselves, natch) were above the law, Cadell instructed them. Even murder was acceptable, if the victim was an inferior.

(David, the movie's victim, went to Harvard, prompting one wag to joke that Brendan and Philip had surely been Yalies...)

What the pair clearly are, are gay lovers, or as "clearly" as the Hays Code permitted. This is not a post-modern "reading" of the movie; everyone on set knew this. Actors Dall and Granger were homosexually inclined, as was screenwriter Arthur Laurents — he was sleeping with Granger during filming — who studded the script with semaphoric winks.

Frankly, making such a gay movie in the mid-20th century was a bigger accomplishment than the whole "one take" stunt. No wonder Rope became a foundational queer film studies "text," subjected to often absurd, but occasionally insightful, analyses: for instance, in defiance of movie convention then and now, Brandon and Philip remain alive at the end.

I find these dissections, in The Celluloid Closet and elsewhere, endlessly fascinating, but what concerns us here is the question of whether or not "words can kill."

Some may object that Rope is just a movie, but others are probably thinking that the plot sounds familiar. That's because (along with a startling number of other films and plays) it was inspired by the real-life Leopold and Loeb case. These two homosexual University of Chicago students murdered 14-year-old Bobby Franks in 1929 because they wanted to commit "the perfect crime."

Infamously, these killers fancied themselves authentic, un-catchable "Nietzschean Supermen" and therefore not only above the law, but the arbiters of a new and better one, in which God was dead, and "superiors" had the right to murder inferiors.

In his 12-hour closing argument, their attorney Clarence Darrow declared it hypocritical to blame Leopold and Loeb, rather than society at large, for putting into practice a philosophy they had been taught in a reputable American school, within living memory of the equally pointless mass slaughter of World War I, no less.

This gambit paid off: Leopold and Loeb escaped capital punishment and were sentenced to life in prison.

In Rope, the shadow of world war is evoked again, this time the recently concluded Second one. As Rupert and Brandon expound on their misanthropic philosophy, David's discomfited father points out that America has just helped rid the world of Hitler, a man who'd been inspired by Nietzsche, too. (Recent scholarship presents a more nuanced take.)

Brandon then launches into a limp condemnation of the Nazis, one which rests more upon their style (or lack thereof) than their substance.

(I wonder how difficult it was for Hitchcock and Laurents to refrain from having him point approvingly to Hugo Boss' SS uniforms, although I feel obligated to add: The pop-history "fact" that gay men wielded inordinate power in the Nazi regime remains disputed.)

The least cogent speech in the movie, however, is Rupert's last:

Almost all the guests have departed, deeply worried about what could have become of David. Rupert remains behind, and deduces that Brandon and Philip have murdered the young man to prove a philosophical point — a philosophy they imbibed at Rupert's feet. (Note Stewart's bandaged palm after a scuffle with the pair: He literally has blood on his hands.)

Having previously insisted multiple times that he was quite serious about wanting to institute "Cut a Throat Week" and other deadly punishments for lesser beings, Rupert now has the nerve to accuse Brandon and Philip of "giving my words a meaning I never dreamed of. You have tried to twist them into a cold logical excuse for your ugly murder."

And on and on, to diminishing effect. What he's saying simply isn't true; the pair have "twisted" zilch — they've followed Rupert's instructions to the letter.

Not even Jimmy Stewart at his most high-pitched and passionate can put this pitiful, incoherent, self-serving word salad across.

This outburst feels so tacked on, it (along with Brandon's lame "I hate Nazis, too" feint) raises the troubling question of what Laurents and Hitchcock genuinely believed; the best that can be said is that, unlike Darrow's oration, it isn't half a day long.

Hell, Otter's speech in Animal House is more persuasive:

Stewart later admitted he'd been miscast as this Discount Oscar Wilde, but honestly, no actor could have CPR'd these moribund words to life. Not even Gary Cooper, for whom I acquired Strange New Respect after learning he'd delivered The Fountainhead's marathon courtroom address the following year, despite claiming he hadn't understood a word of Ayn Rand's paean to — you guessed it — the radical licence of genius.

We on the right tsk a lot about the left's apparently chronic ignorance of the Law of Unintended Consequences.

In Catholic writer Mark Shea's clever formulation, "There are two phases for each period in history. The first phase is called 'What Can It Hurt?' and the second is called 'How Were We to Know?'"

Except increasingly, and for good reason, few of us can in good conscience embrace the conservative catechism espoused by the likes of Ronald Reagan and Dennis Prager that leftists aren't evil, they're just wrong.

By killing David, Brandon and Philip rend a whole family asunder; some critics theorize that David's "crime" (in the murderers' eyes) was rejecting homosexuality by getting engaged, and that his temporary coffin is, pointedly, an antique matrimonial "hope chest."

And anyone who refuses to believe that many gay activists intended all along to destroy marriage and the family; to proudly, publicly violate laws with impunity while persecuting "homophobic" bumpkins who refuse to applaud; to adopt fascist techniques to acquire imaginary "rights"; to have their cake, eat it too, and force you to bake it or else — hasn't been paying attention to the clues.

Alas, even after the mystery — which was never much of a mystery — is solved, the true motives revealed, and the killers exposed, the victim remains just as dead.

Never forget: Today's "fringe belief" is tomorrow's social policy.

Rope is available for streaming at Amazon and elsewhere.

If you enjoyed Kathy's take on this film, let her know in the comments below. If you want to meet your fellow commenters in person, consider joining this year's Mark Steyn Cruise with John O'Sullivan, Michele Bachmann and Conrad Black, among other special guests. Details are available here. Remember that SteynOnline content is made possible by the generous support of Mark Steyn Club members. We're now in our third year of the Club, with lots of great things planned for the coming months. Become a part of them here.