This essay is adapted from Mark's book, A Song For The Season:

I'm not, generally, a big fan of "black history" or "gay history" or most other forms of identity-group history. There is plain old history, which encompasses all of us however peripherally in its whims and cruelties, and, when one tries to narrow the focus to correct longstanding "marginalizations", one too often winds up not with scholarship but with smiley-face boosterism. All that said, let me make an exception to my general antipathy and mark February's "African-American History Month" festivities by noting a songwriter who, in his own way, is a part of both African and American history.

Andy Razaf was born Andreamenentania Razafinkeriefo in Washington DC on December 16th 1895. His maternal grandfather was a freed slave, John Waller - no relation to Fats but a man who had achieved his own success as one of the most prominent Negro diplomats in the US foreign service. Four years before his grandson's birth, Mr Waller had been appointed by the State Department as US consul to the court of Queen Ranavalona III in Madagascar. The island nation did not observe quite the same degree of separation between the heads of state and government as, say, Britain does: in Madagascar, by convention, the Queen's Prime Minister also functioned as her husband. In a relatively short stint as emissary, the ambitious American appears to have endeared himself to the ruling family and, when Grover Cleveland's administration succeeded Benjamin Harrison's in 1893 and the Republican consul was replaced by a Democrat, Mr Waller decided to stay on in Madagascar. The following year, Her Majesty announced that she was granting 225 acres of royal land to the former diplomat to enable him to establish a "colony for American Negroes". Wallerland, as he called his new estate, nevertheless retained close ties to its former owners: Shortly after the land transfer, Waller's 15-year old daughter Jennie was married to Prince Henri, a nephew of Queen Ranavalona.

Alas, the best-laid plans ran afoul of the Quai d'Orsay in Paris, which regarded Madagascar as theirs in all but name and didn't like the growing influence at court of the Negro in-law with connections in Washington. Mr Waller was seized by French troops, convicted by a military tribunal in the port city of Tamatave, manacled hand and foot, and shipped to Marseilles to serve a 20-year sentence. For whatever reasons, President Cleveland's administration did not act on behalf of their national as urgently as they might have, and, in any case, Queen Ranavalona herself surrendered to French troops and left the island. So Waller's family fled, and eventually arrived back in Washington in October of 1895. Nine days before Christmas, 11 days before her 16th birthday, Waller's daughter and Prince Henri's wife gave birth to their son and gave him a Malagasy name: Andreamentania. By then, Prince Henri himself was dead. A graduate of the École Militaire in Paris, His Royal Highness was killed by French troops in their invasion of the island.

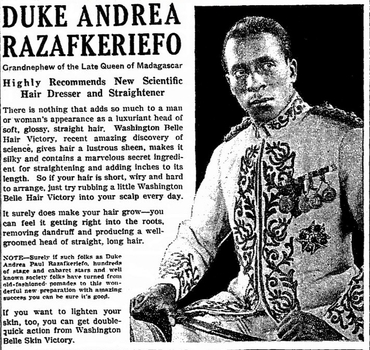

Were it not for the Gallic intervention, Andy Razaf would have enjoyed a royal childhood off the coast of Africa. Instead, he was raised in New York City by a single mom, and at 16 was working as an elevator boy. At 17, he landed his first song on Broadway: "Baltimo'", a late addition to the score of The Passing Show Of 1913. By the Teens and Twenties, there was a lively cadre of black songwriters working on the fringes of Tin Pan Alley, but Razaf's exotic autobiography stood out. He was, to coin a phrase, the artist formerly known as Prince. As The Brooklyn Daily Times reported, with a somewhat cavalier attitude to factual accuracy and elementary internal consistency, "Crooning Grand-Nephew Of Madagascar Queen Possesses Exciting Historical Background":

Because Duke Andre Paul Razafkerie, grand-nephew of Ranavalona III, late Queen of Madagascar, has chosen song plugging as his career, his mother, the Duchess Christian, has refused to have anything to do with him. It is not generally known that 'Crooning Andy,' singing over WCGU every evening, is none other than the Duke himself...

The fall of a kingdom, the fleeing of a royal family, or the capturing thereof, which is ofttimes described in dramatic fashion upon our silver screens, all make up the real life of Andy. During the war of 1890 between the former Malagasy Kingdom and France, the Duchess Christian... returned to her native America, where Duke Paul Andre Razafkerio, who now prefers to be called just 'Andy,' was born...

Andy recently wrote a song, 'Dusky Stevedore,' and highly elated over his new number, he purchased a radio set for the Duchess, and asked her to tune in on the Amberol Hour at WCGU...

"Dusky Stevedore" is a perfect example of what Tin Pan Alley expected from black songwriters – either colorful glimpses of Negro life for white audiences or hyper-sexual lyrics for raunchy black chantoozies. Among the latter, Andy Razaf wound up writing the song that defines the entire genre:

He shakes my ashes

Greases my griddle

Churns my butter

Strokes my fiddle

My man is such a Handy Man

He threads my needle

Creams my wheat

Heats my heater

Chops my meat

My man is such a Handy Man...

And, once you get the general idea, there's no end to the variations:

I got myself a military man

And now I'm almost in hysterics

He's got me in a military plan

You'd think my parlor was a barracks

It's so peaceful when he's gone

When he's home the war is on...

My flat looks more like an armory

He takes his bugle when he calls me

At night he's drillin' constantly

He's My Man O' War

When he advances, can't keep him back

So systematic is his attack

All my resistance is bound to crack

For My Man O' War

He never misses when he brings up his big artillery...

Etc. But eventually even the biggest guns stop firing:

Time after time, if I'm not right there at his heels

He lets that poor horse in my stable miss his meals

There's got to be some changes 'cause each day reveals

My Handy Man Ain't Handy No More

He used to turn in early and get up at dawn

All full of new ambition he would trim my lawn

Now when he isn't sleeping all he does is yawn

My Handy Man Ain't Handy No More...

These songs are adroit and sly, even if they do posit a world of relentlessly single-minded double-entendres. As in English seaside postcards, apparently almost anything in the dictionary can serve as a synonym for the sexual act or the organs required to perform it. One thinks of Britain's Carry On movies and the not entirely plausible scene in which Sid James as King Henry VIII gets his Hampton caught (ie, for non-Brits, a reference to the royal palace of Hampton Court). Razaf was the most inventive author of the "My Butcher's Meat Keeps Going Up" school, but he understood, even then, that it wasn't going to make him Ira Gershwin or Oscar Hammerstein. Ninety-five per cent of the most popular performers on stage, screen, radio and records were never going to go anywhere near such material.

In 1929, the Immerman Brothers, a couple of butchers turned impresarios, hired Razaf and his composing partner Fats Waller to write songs for Connie's Hot Chocolates, an all-Negro revue that would play on Broadway every evening with a repeat performance after midnight in Harlem. Among the numbers the team provided was one which the lyricist's biographer, Barry Singer, calls "Andy Razaf's lyric retort to all the endless bawdy blues variations he'd been forced to compose since the onset of the Twenties." Unlike the lady on the receiving end of "My Man O' War", this young miss is positively demure:

No one to talk with

All by myself

No one to walk with

But I'm happy on the shelf

Ain't Misbehavin'

I'm savin' my love for you...

"The song was ingenuous to a fault," writes Barry Singer in Black And Blue, "modestly affirming home, hearth and devotion to one love, while set against the undercutting drollery of Waller's melody."

How Waller created his most enduring melody depends on whose version of events you believe. Fats was famously feckless and impecunious, even at his peak. Asked in school what his dad did, his son replied, "He drinks gin." In between, he composed and sang and played, brilliantly. But then the gin and multiple other addictions would catch his eye yet again. "Ain't Misbehavin'" he liked to call "The Alimony Jail Song". As Waller told it, at the time he wrote the tune he was incarcerated in said facility, owing 250 bucks to his ex-. He had his lawyer bring him "a miniature piano" and spent two days in his cell writing "Ain't Misbehavin'". His attorney then sold the song to a publisher for $250, enabling Fats to pay off the back alimony and get out of the jailhouse.

Andy Razaf's account of the song's origin is more prosaic. It was created not in jail but in Waller's apartment on 133rd Street in Harlem. During rehearsals for Hot Chocolates, Razaf swung by his partner's place just before midday and found Fats pounding the piano. It was, recalled Andy, "a marvelous strain, which was complicated in the middle. I straightened it out with the 'no one to talk with, all by myself' phrase, which led to the phrase 'ain't misbehavin'", which I knew was the title." Forty-five minutes later, they'd finished the song, Waller got dressed, and the boys headed to the Hudson Theatre for rehearsals. On their way down Broadway to 44th Street, clutching the manuscript, the writers found themselves on the receiving end of a city pigeon who flew overhead and scored a direct hit on the song sheet. "That's good luck!" reckoned Fats. "But I'm sure glad elephants ain't flyin'."

At the Hudson, they scraped the sheet clean and passed it to Harry Brooks, who "arranged" the tune and wound up with a co-composer credit. "You got to hang on to the melody," Fats Waller once said, "and never let it get boresome". In some ways, "Ain't Misbehavin'" was an old-fashioned tune even in 1929, but it never gets "boresome". I especially like the middle section:

Like Jack Horner

In the corner

Don't go nowhere

What do I care?

Your kisses are worth waiting for

Believe me...

The insistent repetition in the tune isn't "boresome" – first, because of Waller's shifting harmony; second, because Razaf varies the lyric scheme: technically, the third and fourth lines should have the same feminine rhymes as the first couplet ("Horner"/"corner"), but instead the author switches to a masculine pairing ("-where"/"care"), which throws the emphases a little off-kilter and keeps things interesting. And after three lines melodically identical, Fats takes the tune up from E flat to E natural on "What do I care?" and gives the words real feeling. The chorus concludes with a lovely cozy image:

I don't stay out late

Don't care to go

I'm home about eight

Just me and my radio...

I used to like it when Bing Crosby would do "Ain't Misbehavin'", and sing:

I'm home about eight

Get Clooney on the radio...

- as in his pal Rosie. In the wake of Hot Chocolates, "Ain't Misbehavin'" was a hit not just for Waller and Louis Armstrong but Gene Austin and Paul Whiteman, too – and in the years that followed it was picked up by Billie Holiday, Guy Lombardo, Django Reinhardt, Stephane Grappelli, Art Tatum, Jimmy Dorsey, Nat "King" Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Chet Atkins, Johnnie Ray, Frankie Laine, Andre Previn, Gwen Verdon, Louis Prima, Miles Davis, Tommy Bruce & the Bruisers, Ray Charles, Vic Damone, Leon Redbone, Hank Williams Jr, Asleep At The Wheel, the Brigham Young University Young Ambassadors... In others words, by everybody, give or take.

There was another song in Hot Chocolates. One afternoon, Dutch Schultz, the mobster and a big backer of the production, came up to Razaf during rehearsals and said the show was pretty good so far but he'd had a great idea for a song that would make it a surefire smash: A dark-skinned woman is lying in a white negligee on white sheets in a white bed in an all-white room, and she's singing this funny song about how she's too black and the lighter-skinned gals get all the guys. That'd be pretty cute, right? When the lyricist politely demurred, Schultz pinned him to the wall, pulled out his gun and put it to Razaf's head: "You'll write it," he said, "or you'll never write anything again."

Razaf and Waller decided to subvert the assignment. On opening night, there was Edith Wilson on a set more or less as ordered up by the gangster. And the early verses of the song – "Browns and yellers/All have fellers/Gentlemen prefer them light..." – certainly drew the laughs Schultz had predicted. But, as the song went on, it became clear, both in the mournful melody and the lyrics, that Waller and Razaf had enlarged the subject profoundly:

Just 'cause you're black

Folks think you lack

They laugh at you

And scorn you too

What did I do to be so Black And Blue?

It was a remarkable song for 1929, and all the more so for Razaf on the first night, with Dutch Schultz standing next to him and ready to kill him if "Black And Blue" had bombed with the audience. Half a century later, in Ain't Misbehavin', the Broadway revue celebrating Waller's world, it was the song the creators of the show chose to end the evening with. Yet, powerful and impassioned as it is, there would be something wrong and reductive in letting it stand as the final word on its author.

Andy Razaf was certainly black and he had plenty to be blue about. The son of a prince, and grandson of one of the most eminent black Americans of his day, he suffered racism both of the small routine everyday kind and on a geopolitical scale: the annexation by the French of the land his family ruled. He recovered from that setback to become the most successful black lyricist the American music industry had ever seen, and yet even then there were avenues that remained closed off. Unlike almost every other name songwriter working in New York in the late Twenties, he was never offered big money to come out to Hollywood and write pictures. But he kept going, and so did the songs. "Ain't Misbehavin'" - like "Honeysuckle Rose", "Keepin' Out Of Mischief Now", the sublime "Memories Of You" and the other peaks of the Razaf oeuvre – belongs not merely to "African-American history" but to American history, and the soundtrack of the nation:

I don't stay out late

Don't care to go

I'm home about eight

Just me and my radio...

The radio's changed a bit since Andy Razaf's day, but they're still playing his songs:

Ain't Misbehavin'

Savin' all my love for you.

~adapted from Mark's book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the Steyn store.