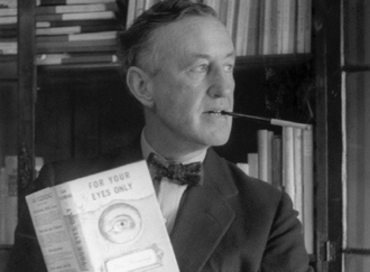

To mark today's premiere in London of the new Bond film, Spectre, SteynOnline is offering its own quantum of Bondage this week, starting with our tip of the hat to 007 screenwriter Christopher Wood. Today we go back to where it all began, with Bond on the page - and his creator, Ian Fleming. This very popular essay comes from Mark's book The [Un]documented Mark Steyn, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore:

His first draft would have been good enough for most of us:

Scent and smoke and sweat hit the taste buds with an acid thwack at three o'clock in the morning.

But he wasn't happy and tried again:

Scent and smoke and sweat can suddenly combine together and hit the taste buds with an acid shock at three o'clock in the morning.

Still not quite there. So he rewrote once more, and this time he skewered it precisely:

The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling - a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension - becomes unbearable and the senses awake and revolt from it.

James Bond suddenly knew that he was tired.

It was January 15th 1952, and Ian Fleming - a middle-management newspaper man - had sat down in his study at Goldeneye, his home in Jamaica, opened up a brand new typewriter (gold-plated), and begun the first chapter of his first book. Conceived as a bestseller, Casino Royale effortlessly transcended such unworthy aims. Today, its protagonist is up there with Count Dracula and Batman and a handful of other iconic A-listers. Fleming did not anticipate what to me is always the dreariest convention of the celluloid Bond blockbuster - the final 20 minutes in which 007 and the girl run around a hollowed-out mountain or space station or some other supervillain lair shooting extras in BacoFoil catsuits while control panels explode all around them and Bond looks frantically for the big red on/off button that deactivates the nuclear laser targeting London, Washington, Moscow and/or Winnipeg. But, that oversight aside, it's remarkable how much of the 007 architecture the novelist had in place so quickly. In Casino Royale, the roulette table shows up on page one, M on page three, Moneypenny on page 13, the Double-Os on 14, the CIA's Felix Leiter on 31, the first dry martini, shaken not stirred, on page 32. "Excellent," pronounces Bond on the matter of the last, "but if you can get a vodka made with grain instead of potatoes, you will find it still better."

So five chapters in and Fleming's invented most of the elements propping up the formula for the next five decades. That's not to say he was formulaic. Au contraire, that's the big difference between the Bond books and the Bond films: Fleming eschewed formula. Sometimes he put 007 up against evil megalomaniacs bent on world domination; but he also wrote The Spy Who Loved Me, a tale of small-time hoods told by a young woman (une jolie Québécoise, as it happens) in which Bond doesn't turn up until halfway through; and From Russia With Love, with its unhurried Bond-free Soviet prologue; and a dozen or so short stories, one of which - "Quantum Of Solace" - is little more than a dinner-party anecdote told to Bond by a colonial civil servant. Fleming had such confidence in his character's adaptability to form it's a wonder he didn't put him in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

By contrast, the films settled into their groove early and were disinclined to depart therefrom. So we've had four decades of the pre-credits sequence, the song, the titles with the naked girls morphing into pistols and harpoons, Q saying "Oh, grow up, 007", the double entendres ("I'm afraid something's come up"), etc. Whether it's a smart move to dump it all, as the new Casino Royale does, remains to be seen. But, as with the allegedly stale formula, almost all the "new" gritty, tough Bond comes direct from Fleming.

Not that he gets much credit either way. In his anthology of espionage fiction, Alan Furst explains that "there were two standards for the selections in The Book of Spies: good writing - we are here in the literary end of the spectrum, thus no James Bond - and the pursuit of authenticity".

My, that's awfully snooty. It's not clear to me that Fleming is any less "authentic" than, say, John Le Carré. Certainly, an organization such as SPECTRE seems more relevant to the present globalized alliances between jihadists, drug cartels, and freelance nuke salesmen than anything in The Russia House. Indeed, to assume the murky moral ambiguity of Cold War wilderness-of-mirrors spy fiction must be "authentic" indicates little more than political bias. There's no evidence the vast majority of MI6, the CIA or the KGB saw it like that, and as to the general glumness of pre-swinging London, Fleming's far more evocative than the "authentic" chaps:

He thought of the bitter weather in the London streets, the grudging warmth of the hissing gas-fire in his office at Headquarters, the chalked-up menu on the pub he had passed on his last day in London: 'Giant Toad and 2 Veg.'

He stretched luxuriously.

As for "good writing" at the "literary end", Furst is on thin ice here with his cringe-makingly clunky sex scenes in which (speaking of literary ends) characters "ride each other's bottoms through the night", which makes them sound like Paul Revere fetishists. For all his famously peculiar tastes, Fleming had a careless plausibility in this area: I like his line that "older women are best because they always think they may be doing it for the last time". Like the best Fleet Streeters of his generation, he was an extremely good writer, at least in the sense that he was all but incapable of writing a bad sentence. Do you know how rare that is in this field? The bestselling author David Baldacci, for example, is all but incapable of writing a good sentence, though it doesn't seem to make any difference to sales of Absolute Power, etc.

It's essential for thriller writers to conjure the details convincingly: in Casino Royale, one notes, the wire transfers are effected via the Royal Bank of Canada. But it was never about the numbingly nerd-like annotation of the "pursuit of authenticity". With his fanatical insistence on ritualized cocktails, and cigarettes (Morland) and breakfast menus (Cooper's Vintage Oxford Marmalade), Bond prefigured much of today's brand-name fiction. Consumer name-dropping was a novelty in the drab British Fifties, and, of course, unlike chick lit and Hollywood soft porn, there's something pleasingly goofy about a fellow who spends so much time getting beaten and tortured by cruel men in the shadows and then gets hung up not only about which caviar and which Bollinger, but which strawberry jam (Tiptree "Little Scarlet") and which nightshirt ("Bond had always disliked pyjamas and had slept naked" until in Hong Kong he had discovered "a pyjama-coat which came almost down to the knees"). Fleming's 007 is a paradox: he prizes habit but dreads boredom. As he muses to himself in Casino Royale:

He found something grisly in the inevitability of the pattern of each affair. The conventional parabola - sentiment, the touch of the hand, the kiss, the passionate kiss, the feel of the body, the climax in bed, then more bed, then less bed, then the boredom, the tears and the final bitterness - was to him shameful and hypocritical. Even more he shunned the mise en scène for each of these acts in the play - the meeting at a party, the restaurant, the taxi, his flat, her flat, then the weekend by the sea, then the flats again, then the furtive alibis and the final angry farewell on some doorstep in the rain.

That's beautifully poised: "then more bed, then less bed." It's all the better because Bond thinks he means it. Fleming understood the sleight of hand involved in each book - the strange disquisitions on short men or American road signs or the ghastliness of tea that glide you over the not quite convincing plot twist and on to the next magnificent set piece. He kept it up almost to the end, until sickness and boredom ground him down.

But, as an exercise in sheer style, the Fleming of Casino Royale is hard to beat. It's not about the plot. Unlike almost any other thriller writer, he can be read over and over and over.

~adapted from from Mark's book The [Un]documented Mark Steyn, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore - or double your pleasure and get it with Mark's very own recording of "Goldfinger"!